Rubik’s Cube Event

(13 mins read) On the 11th of November, Christ’s College hosted an incredible event to celebrate the history of puzzles in mathematics, with a special recognition of the 50th anniversary of the Rubik’s Cube. In this article, Dhruv Shenai, President of Darwin Society, takes us through the details of the event. Hopefully, it shows the type of events you can attend at Cambridge!

On the 11th of November, Christ’s College hosted a diverse panel celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Rubik’s Cube and how it links to the wider world of puzzles. With venerated names such as GM Judit Polgar and Ernő Rubik himself present (discussed at the end), it was bound to be a packed event brimming with ideas. In this article, we’ll explore what was said and what it can teach us about Puzzles, Mathematics, Autism and Chess.

The Morning session

Autism and Puzzles

The day started off with a panel discussion on how we understand autism.

Panel including Professor Sir Simon Baron-Cohen, Jim Hogan, Professor Jenny Gibson, Professor Imre Leader and the chair: Paul Ramchandani

Professor Sir Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Cambridge Autism Research Centre, introduced the research done on autism and how we interpret the results. He described a correlation between autism and ‘pattern-seeking’ abilities which he calls ‘systemizing ability’. He used his research to argue that autistic people tend to tackle geometrical puzzles (experiment and find patterns) better than ‘neurotypical’ people. More on his research can be found online, but it did raise some questions in the audience.

Professor Sir Simon Baron-Cohen talking on the topic of Autism

For example, whilst the research tries to argue that autistic people are ‘different, not less’, it still feels like the messaging is presented as comparing autistic people to ‘neurotypical’ people. Many in the audience were left feeling like the message didn’t really go far enough to validate the experiences of autistic people.

In essence, by highlighting the strengths of some autistic people, especially this pattern-seeking ability, it unintentionally sends a message that we are narrowing the way we value or understand autistic people: we only celebrate those who perform difficult feats. Whilst these people are no doubt exceptional and deserve to be praised, those who may not connect with or feel like they excel in ‘systemizing abilities’ could feel marginalised in a group that is already marginalised enough. Whilst this is probably not the belief of Professor Baron-Cohen, perhaps there is a better angle to approach the research from.

The messaging may need to open up to the wider community, including those that struggle with autism as a disability. Especially with around 80% of autistic people being unemployed, there is a demand for encouragement and support – not just monetisation of their abilities. To the professor’s defence, he did make it very clear that more support is required, and he has expanded on these ideas at other, longer format talks.

The next speaker provides an alternative outlook to the field of Autism Research.

Jim Hogan, Chief Innovation Evangelist at Google Cloud, describes how autism shaped his own life. Being autistic himself, he recounted the tale of his diagnosis. “This was in the 70s, so a great deal has changed since then, but I vividly recall the doctors telling my parents ‘he’s [Jim] going to be a burden on you for the rest of your life’,” said Jim.

He talked about how his life balanced not wanting to be a burden with wanting to explore the technological world around him. “I was fascinated by every household device. If I was left alone in the kitchen, I’d dismantle the toaster and try and work out its components. If I was alone in another room whilst my mum was on the phone to my auntie, I’d be dismantling the other landline phone trying to find out how it worked… My mum wasn’t quick to be supportive, but my dad was always there for me. He was the one who used to say ‘Do you want to know how that works?’” said Jim, “and that’s what really pushed me to get into telecommunications research and eventually lead me to my job at Google.”

When discussing his experience with Autism research, Jim mentioned how all they did was try and test him. “They used to give me all these physical puzzles to solve, and I would just be no good at them. I really didn’t like them,” said Jim. It shows that not everyone shows the systematizing abilities Professor Baron-Cohen posits.

Jim also pointed out how he prefers the term ‘neurodistinct’ rather than ‘neurodivergent’ as he ‘would rather be called physically distinctive than physically divergent’. This again shows how the research tries to umbrella a large population, who all have their own opinions and preferences. Jim also said how the word choice of ‘neurodivergent’ fails to acknowledge how everyone in the world thinks differently, even one autistic person to the next.

Jim is evidence how autistic people can succeed in the workplace and how workplaces can improve their accessibility and diversity to be inclusive to all people.

Professor Jenny Gibson added to the discussion with her own work on play and puzzles and how it links to neurodiversity. She talked about autism’s portrayal as a ‘tragedy’ and how, in reality, it is nothing of the sort. She argues that we should celebrate, not ‘mourn’ autism.

Professor Jenny Gibson lecturing on the link between neurodivergence and play

“Autism is a way of being. It is pervasive; it colours every experience, every sensation, perception, thought and emotion, and encounter, every aspect of existence,” said Jenny, quoting Jim Sinclair, founder of Autism Network International, who helped pioneer the neurodiversity movement.

She added how historically women were not being properly diagnosed with autism, instead being diagnosed with other disorders or otherwise being dismissed. She also mentioned how the evidence suggests that female autism may present differently than male autism with issues like ‘masking’ cropping up more frequently. She called for the continuation of female autism research, stating how though it has improved, there is always more work to be done to catch up.

There was also a brief interlude from Professor Imre Leader, Professor of combinatorics at Cambridge University, who discussed the prevalence of autism in the mathematics department at Cambridge.

Demonstrations of Exceptional Talent: Max Park and Derek Paravicini

After a minute’s silence, the panel was followed up by wonderful demonstrations and reflections by Max Park and his father, Schwan Park, as well as Derek Paravicini and his piano teacher, Adam Ockleford. They discussed how, though their autism has presented many challenges, they also have this fascinating ability to find patterns. In the case of Max, he can solve the Rubik’s Cube quicker than anyone else (he holds the World Record of 3.314 seconds) and actively enjoys doing so. For Derek, he can express himself through his music and experiment with the musical motifs he has heard from other pieces.

Performance from Derek Paravicini, @derekparavicini on youtube

Event organiser, Paul Fannon OBE, Assistant Professor of Mathematical and Computational Biology at the University of Cambridge shared his amazement and admiration after the demonstrations saying, “never have I sat for 30 minutes just shaking my head in disbelief, going ‘how is this possible?’” For the audience, it was a moment of awe, allowing them to get absorbed in the brilliance of two amazing individuals.

Afternoon Sessions

AI, the Rubik’s Cube and Puzzles

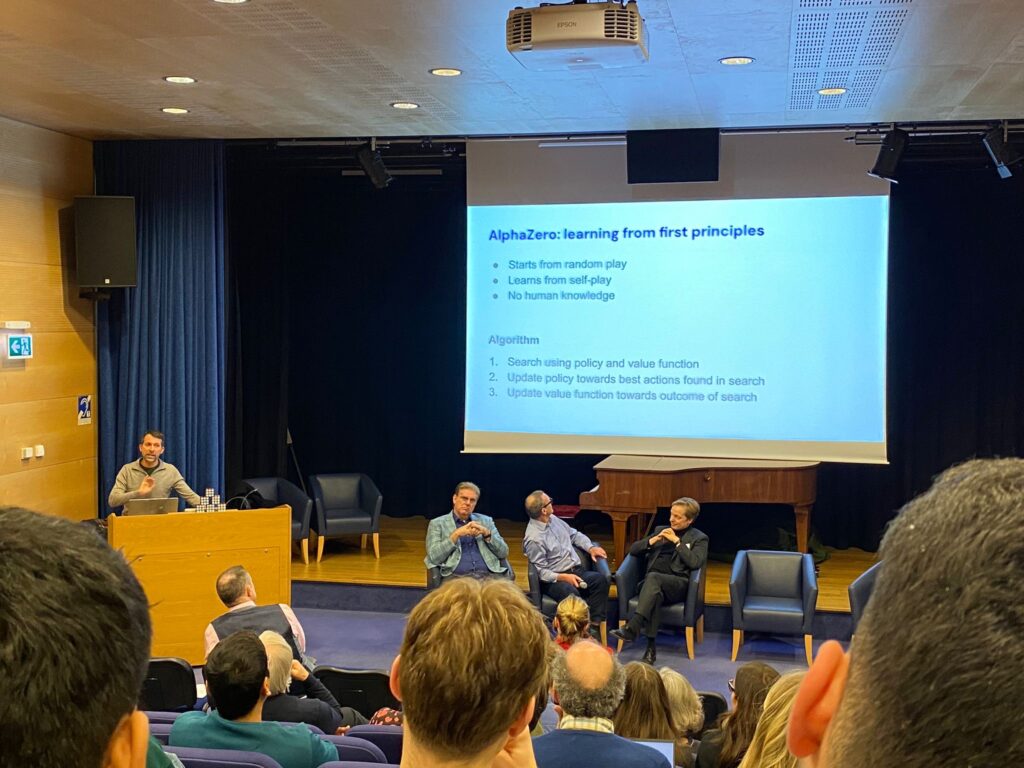

David Silver, from Google DeepMind, talked about how AI can be used to solve puzzles as well as board games. He demonstrated how Reinforcement Learning can be exploited to build models from scratch to play many games at the highest level, from Atari’s Space Invaders, to Go, Shogi and Chess. In particular, he discussed what it was like making AlphaGo, a model that eventually beat the best human players at Go.

David Silver (Google DeepMind) lecturing on AlphaGo, a machine learning program.

An extremely popular event amongst the audience, many members of the audience asked David what his thoughts on AI’s future was. David discussed how AI will continue to be used to solve a much wider set of problems, including ones not currently solved, like certain mathematical proofs. He hopes that models will continue to become quicker and perform at higher and higher levels.

Next, Professor James W.P. Campbell from the University of Cambridge discussed the role of the architect and his fascination with the Rubik’s Cube. Questions such as ‘why does the Rubik’s cube have three primary colours but only two secondary colours, replacing purple with white?’, ‘how do you design the inner mechanism of the cube?’, ‘what materials do you use for the cube?’ are all questions he thinks an architect should ask. Disappointingly, he didn’t reveal the answers to any, but it left much room for thought. The Rubik’s Cube is undoubtedly genius in its simplicity whilst preserving function.

Finally, Jim Hogan returned to discuss how Google uses puzzles. He described his old interview questions and how they show a desire to understand the thought process behind the applicant, similar to Cambridge interviews. He then summarised how autism played a role in defining who he is and how he got into Google.

Puzzles and Mathematics

After a short break, the conversation shifted to Mathematics, its role in society and link to puzzles. Professor Sir Tim Gowers FRS, Fields medallist and professor of combinatorics at Cambridge, talked about his work creating a game that hides formal mathematical proofs inside other puzzles. Through this medium, he tried to express how a machine would think: it is simply presented with the problem and has to try and solve it without knowing the context behind it. This is partly what goes on in reinforcement learning; the AlphaGo model itself doesn’t know that the game is called Go, it just knows the next move. Humans are constantly surrounded by context, and perhaps by understanding instead what a computer sees, Tim believes that we can bridge the gap in understanding between AI and humans, leading to better governance of AI technology.

Next, Professor Gábor Betegh, Professor of Ancient Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, gave a historical account of the development of key ideas in maths. Analysing figures such as Plato and Socrates, to Pythagoras’s theorem, he provided a full exploration of the brilliant work done in mathematics in Early Greece.

As Chair of the United Kingdom Mathematics Trust (UKMT), Professor Geoff Smith MBE discussed how mathematical Olympiads are being challenged by AI, but also its importance for budding mathematicians. He started by discussing how brilliant mathematicians are brought down by the slog of ‘question after question’ in mathematics at school. He instead proposes that puzzles are required to present a challenge and make it fun for students. This shows why the maths Olympiad is so important – to train mathematicians to think about challenging problems and introduce them to university level mathematics.

About AI, he hypothesises that there is still some way to go for the AI models, but that conventions must be put in place to counteract its use.

Next Dr Henry Bradford, Director of studies in Mathematics at Christ’s College, talked about the group theory behind the Rubik’s Cube. He introduced the proof that the Rubik’s Cube can always be solved optimally in less than 20 moves and how we might come about that. He also explained what a group is, and what its use is in mathematics.

The session was finished with an interlude from Dr Christie Marr, executive director of the Academy for the Mathematical Sciences, who informed the audience on the guidance that the academy can provide to the budding mathematician. She spoke about how the academy houses people from a wide variety of mathematical applications, and how there is someone useful to talk to for everyone.

Puzzles and Education

After a break, the conversation again shifted, with a new panel consisting of a wide range of maths communicators, to discussing the importance of puzzles in maths education.

Rob Eastway lecturing on the use of puzzles in Education.

On the panel was Rob Eastaway, author of ‘Why do buses come in threes’; Brady Haran OAM, creator of the ‘Numberphile’ YouTube channel; Simon Singh MBE, author of ‘The maths of the Simpsons’, ‘Fermat’s Last Theorem’ and ‘The Code book’; Conrad Wolfram, from Wolfram Research (which created WolframAlpha and Wolfram Mathematica); GM Luke McShane, chess grandmaster and Dr Vesna Kadelburg, leader of the UK Maths team and advocate for the Mathematics Olympiad for Girls (MOG).

Personal highlights from the talk came from Vesna who illustrated the improving participation of girls in maths competitions and the positive signs this shows, Rob who showed some of his favourite mathematical puzzles and Luke in discussing the link between mathematics, chess and puzzles.

After an audience question, a heated discussion broke out on the way we bring in children from an early age into mathematics. Brady talked about how he always gets asked ‘what car do you drive?’ and how this shows that kids that ask it care about different things like being rich and successful. Simon argued that kids aren’t wholly motivated by cars and whether Brady has a fancy car won’t change whether kids go into maths. He instead suggests that the small percentage of students that love maths, will remain in maths and it’s more about discovering them rather than creating them.

Whilst I’m sure it’s more complicated than cars, the discussion has an important underlying question: how do we tailor STEM communication to bring in children who would have been interested in STEM, but are put off it by social pressures and a lack of opportunity? This links back to the work done by Vesna on girls’ participation in maths Olympiads. Whilst every member on the panel seems to be producing content for those that already lie in STEM, there is a real demand to break through to those that need just that extra bit of confidence to pursue a career in STEM. Brady’s point about the cars brings forward a more general question about how we advertise the field to students.

With the afternoon of talks over, the event then forked into two separate events, a series of demonstrations from speedcubers and a Chess challenge featuring Cambridge’s Blue’s Chess players captained by grandmasters Judit Polgar and Luke McShane. This was an enjoyable time for refreshments, conversation with others at the event and some exciting puzzles!

Chess game in Christ’s College’s Formal Hall

The Evening Chat

GM Judit Polgar

The day ended with a fireside chat (no fire present unfortunately) with Ernő Rubik and GM Judit Polgar.

Judit Polgar and Ernő Rubik in discussion with Paul Ramchandani

Judit described her childhood – about being homeschooled by her parents – and the way that let her devote her time to chess. She talked about the misogyny she faced and observed during her rise to grandmaster. Whilst she insists it’s getting better, she is aware that more needs to be done in every facet: the parents, the coaches and the chess organisations all must be better at supporting women and other minorities.

Judit emphasised how being homeschooled was a double-edged sword for her. On the one hand, she was initially protected from the prejudice, but on the other hand, it hurt her a lot when the misogyny eventually caught up to her. She gave anecdotes describing how one grandmaster jokingly remarked after playing chess with a female opponent “now who do I play? A dog?”, and how many of her opponents would lie and say they were not well and that’s why they lost to Judit. “A lot of sick people played me,” joked Judit.

Judit then talked about the importance of puzzles and the role that chess could have in education. “Puzzles are like magic to me,” said Judit, “I definitely see puzzles and chess being used in the curriculum. It is already true that in some countries like Armenia, chess is already compulsory to their education. There is an argument against forcing people, of course, but I do think we should be introducing it into schools as a fun exercise. Part of my work nowadays is creating a course that uses chess as an educational tool rather a means to be better at the game.” Her hope is that this and much more can be more widely introduced into schools to encourage learning through play.

Ernő Rubik

Finally, we ended the day with reflections from Ernő Rubik himself. Reflecting on the Rubik’s Cube’s impact, Ernő Rubik discussed how puzzles influence our daily lives. “You can either say that you are creating or discovering. I personally think I am the discoverer of the Rubik’s Cube, not its creator. These puzzles exist just waiting to be found and solved. When I discovered the Rubik’s Cube, I was exploring a concept,” said Ernő Rubik.

He discussed his thoughts on its use today. For example, he was quite interested to see that the cube could be solved optimally at most in 20 moves, however he says that’s not the reason he made the cube. The optimal solution is not interesting but instead the methodology of getting to the answer in the human way, through algorithms, is. He mentions how being an architect were necessary steps to help him become who he was, and thus make the Rubik’s Cube. However, he does say that he finds it funny how no one knows him for any of his buildings or architectural work.

In conclusion, the Rubik’s Cube is an emblem of algorithmic puzzles, inspiring millions to experiment and get involved in puzzles. Puzzles have become incredibly important as a resource – to educate and inspire the way we communicate maths and learn. Without puzzles, mathematics would be a boring landscape. To go further, puzzles are integral to mathematics itself, and the latter could not exist without the former.

The simplicity of the Rubik’s Cube makes it accessible to all, but an innate understanding of it is achieved by the brilliant pattern-recognising humans who do their best to solve it. As research into autism continues to grow, hopefully more work is done to improve the messaging, raise awareness, and continue to support the neurodivergent community. Today was a brilliant day for Christ’s College and its audience members, and I can only wholeheartedly thank the event organisers for creating such a brilliant event.

So, let’s name them! Firstly, I thank Paul Fannon, for his amazing contacts and brilliant event organisation skills. To plan, create and execute this event in under 6 weeks is a monumental task that I’m not sure anyone else I know could have done.

l-r: Vesna Kadelburg and Paul Fannon with GM Judit Polgar

I also thank Ernő Rubik, for choosing this college and bringing in the calibre of guests that they did. I’d also like to thank Gábor Betegh for their contributions to the event organisation included the succeeding conference dinner for the speakers. Finally, I’d like to thank all the Speakers, the Chairs and Demonstrators as well as the audience that asked insightful questions and made this event respectful and engaging.

About the author:

Hi! My name is Dhruv Shenai and I’m a third-year undergraduate in Natural sciences. As a student of Paul’s, and a budding science communicator, I volunteered to help write this report. Therefore, I wanted to add a disclaimer that all things here that can be construed as an opinion are through my inexperienced eyes. There are also many other opinions not presented here which would have enriched this report. So, I apologise if I get anything wrong, or if I misremembered a particular section. I encourage you all to add your own comments and corrections online and add to the discussion. To conclude, it was an absolute pleasure to help with the reporting and photography of the event and I hope you all enjoyed reading my recount. I tried to stay impartial; I promise. 😊